TARS: Interstellar-Grade AI on an ESP32-C3 Super Mini

1. Summary

Bringing the “Endurance” to the Edge.

“Honesty is ninety percent.” But when it comes to embedded AI, efficiency is everything.

In a landscape saturated by closed-ecosystem smart speakers that treat users as data points, I set out to build TARS: a fully custom, privacy-focused voice interface housed entirely on the stamp-sized ESP32-C3 Super Mini.

The Scavenger Constraint: Inspired by the gritty, functional aesthetic of Interstellar, I imposed a strict rule on myself: Total Hardware Autonomy. I refused to buy new specialized components, opting instead to use only what I already had in my parts bin or could salvage from the literal trash. TARS wasn't just built; he was scavenged.

This project streams raw PCM audio from a $3 microcontroller to a custom Python brain, processes intent with local or private LLMs, and returns synthesized speech in real-time. It demonstrates that with rigorous memory management, custom protocol optimization, and a bit of grit, even the most constrained (and recycled) hardware can drive sophisticated, conversational AI.

2. The Challenge

“The Infinite Hiss” and the 400KB Ceiling.

The objective was deceptively simple: “Hey TARS, what's the weather?”

To achieve this, the system needed to: 1. Listen for a wake word locally (or stream for server-side verification). 2. Capture high-fidelity audio. 3. Stream that audio to a FastAPI backend. 4. Play back the generated response via an I2S amplifier.

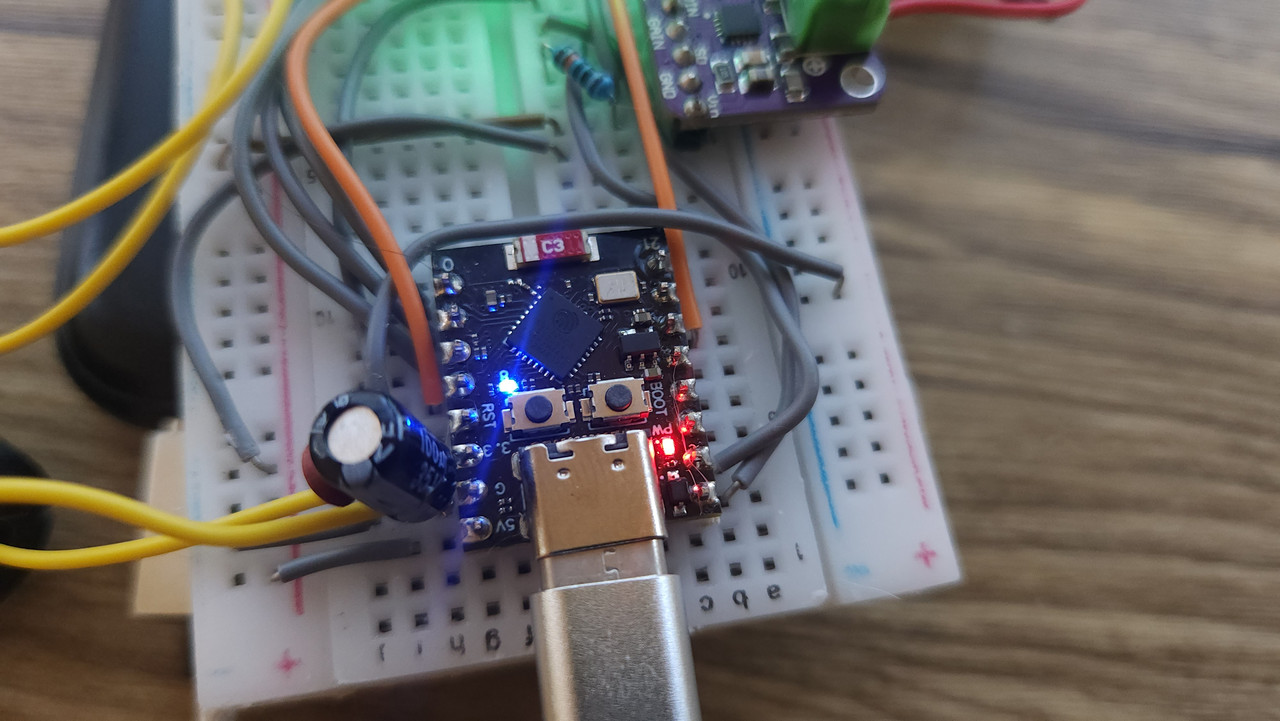

However, the ESP32-C3 Super Mini is unforgiving. It features a single-core RISC-V processor running at 160MHz with limited SRAM. Sharing this single core between the aggressive Wi-Fi stack and my real-time audio application created a “stability crisis” I dubbed the Zombie State.

3. The Hardware Interface (The Body)

“Come on TARS.”

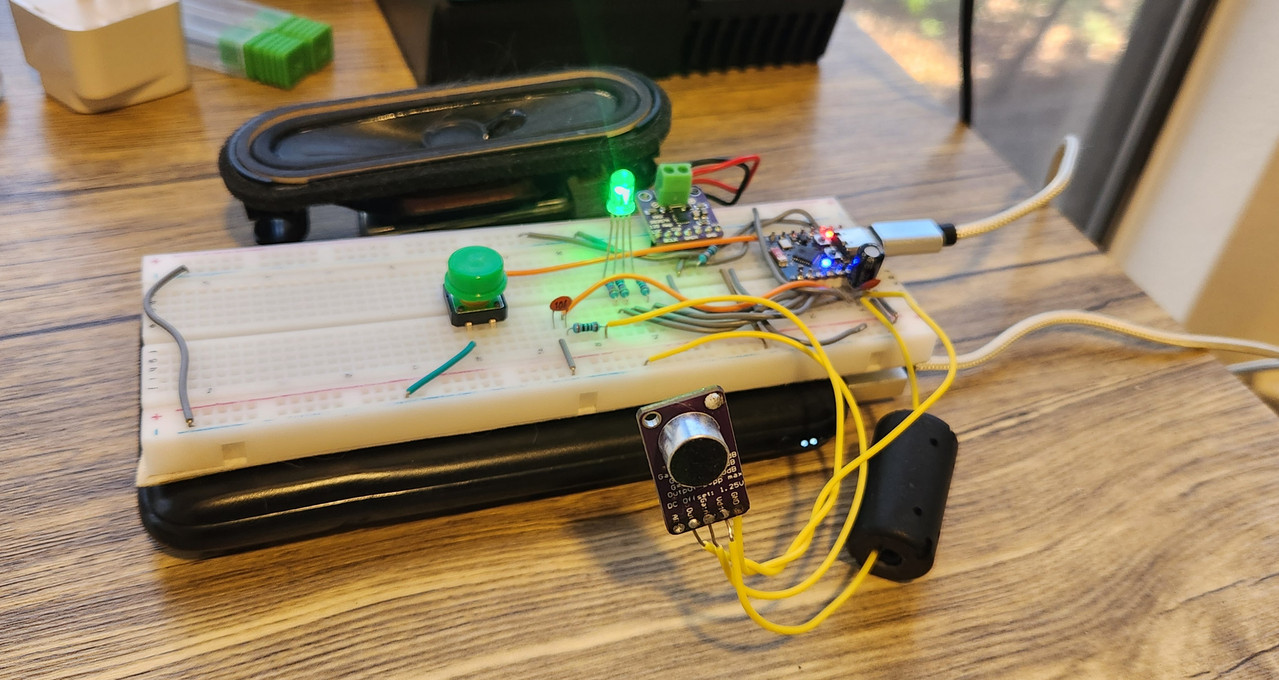

The physical construction of TARS had to be minimal but functional. I chose the ESP32-C3 Super Mini for its incredibly small footprint, but the “brains” needed a body made of scavenged parts.

The Salvage List:

The Voice: The internal speaker was pulled from a broken LCD TV I found in my apartment complex's dumpster. It’s surprisingly high-quality for mid-range frequencies. The Noise Floor: To stop power supply noise from ruining the microphone's signal-to-noise ratio, I used a ferrite bead stolen from a discarded power lead. I placed this on the VCC line feeding the microphone to filter out high-frequency interference before it hit the ADC. The Rest: Every resistor, jumper wire, and the breadboard itself were components I already had laying around from years of half-finished projects.

The wiring required some real precision to avoid strapping pins that would prevent boot:

Microphone (MAX9814): Connected to GPIO3 (ADC). The salvaged ferrite bead keeps the 3.3V line clean.

Amplifier (MAX98357A): A standard I2S amp driving the salvaged TV speaker. The critical connections: BCLK (GPIO5), LRC (GPIO4), and DOUT (GPIO6).

Feedback (RGB LED): To give TARS personality, I wired a common-cathode RGB LED to PWM pins (GPIO 0, 1, 2).

4. The Ear: Digital Signal Processing

“Setting Cue Light to 100%.”

Standard analogRead() is too slow for high-frequency audio capture. It blocks the CPU and starves the Wi-Fi stack, which is catastrophic when you are trying to stream audio in real time. My solution was to bypass the high-level APIs and interact directly with the hardware's ADC Continuous Mode via the ESP-IDF drivers. This lets the DMA engine fill a ring buffer in the background while the CPU keeps the network alive.

// Hardware-level continuous ADC reading

bool capturePcmChunk(int16_t *buffer, int count) {

// Reads directly from the hardware ring buffer filled by DMA

esp_err_t err = adc_continuous_read_parse(gAdcHandle, parsed, kAdcReadMaxSamples, &numSamples, 100);

// ...

}

Cleaning the Signal

Raw ADC data is ugly. It has DC offset, low-frequency rumble, and high-frequency grit. I used a lightweight integer filter chain inside the capture loop: High-pass to remove DC bias and wall hum. Low-pass to smooth quantization noise. Scaling to map the signal into 16-bit PCM.

int centered = raw - 2048;

int32_t y = centered - hp_x_prev + (hp_y * kMicHpCoeff) / 32768; // High-pass

hp_x_prev = centered;

hp_y = y;

lp_y += ((hp_y - lp_y) * kMicLpCoeff) / 32768; // Low-pass

int scaled = (int)lp_y * kMicScale;

buffer[i] = (int16_t)scaled;

The goal was not audiophile fidelity. The goal was a clean, consistent envelope that Whisper can decode without hallucinating.

Energy and Silence Detection

I compute average absolute amplitude per chunk to do two things: LED feedback (brightness mapped to mic level). End-of-speech detection so I stop recording as soon as the user finishes talking.

This let me keep recordings short and predictable, which matters because every extra second is latency and extra load on the STT model.

Chunking and Gate Logic

Audio is sent in fixed 100 ms chunks. The server expects 16 kHz PCM, so each chunk is exactly 1600 samples. That predictability is why the server can handle it without expensive resampling.

I also built a speech gate mode (off by default) that buffers a few “pre-roll” chunks so TARS does not clip the start of a sentence. When enabled, it waits for energy to cross a threshold, then sends the pre-roll plus the active speech window. This makes the system more forgiving to quiet voices and slow starts.

Why This Matters

If the audio pipeline is unstable, nothing else works. Bad audio means broken STT, which means garbage replies, which means the user loses trust in the system. The DSP layer is where the project either feels alive or feels like a dead chatbot.

5. The Brain: Server-Side Intelligence

“I have a cue light, I can use it to show you when I'm joking.”

The firmware is only half the story. The brain of TARS is a Python FastAPI server running on my Debian based home server. This is where the actual intelligence lives: wake-word detection, speech-to-text, tool execution, and text-to-speech. The ESP32 is the body. The server is the mind.

At a high level, the server has four jobs: Listen: Accept raw PCM audio and decide if it is a wake word or a full request. Think: Route the transcript through tools and LLMs. Speak: Generate TTS audio and return it as a clean, finite stream the ESP32 can safely consume. Explain: Expose debug endpoints so I can see state without touching the microcontroller.

The key is that the server stays modular. I can swap models, change tools, or add entirely new behaviors without reflashing the ESP32.

The “DSML” Protocol

I needed TARS to be able to perform actions—like checking the time or searching the web—without the overhead of complex function-calling schemas that often confuse smaller models.

I invented DSML (Domain Specific Markup Language), a pseudo-XML format that is token-efficient and easy for models to generate.

# app.py: Parsing the custom tool protocol

def _parse_dsml_tool(content: str) -> Optional[Tuple[str, Dict[str, str]]]:

name_match = re.search(r'<[||]DSML[||]invoke name=\"([^\"]+)\"\s*>', content)

if not name_match:

return None

This simple regex-based parser allows the LLM to output <|DSML|invoke name="get_weather">, which the server intercepts, executes, and feeds back into the context before generating the final speech response.

The Core Pipeline

The server accepts two kinds of audio:

Wake-word streaming to /ingest in 16 kHz PCM chunks.

Full utterance capture to /speech as one contiguous PCM blob.

From there the flow is precise:

1. Wake: /ingest runs an openwakeword ONNX model on a rolling buffer and returns a score + trigger flag.

2. Capture: /speech runs Faster Whisper on the exact PCM stream the ESP32 sends.

3. Reason: The transcript is passed into the LLM along with tool and memory context.

4. Return: The server responds with a reply and a tts_id so I can trace it end-to-end.

Tools, Memory, and the “Fake OS”

DSML is only one piece of the tool layer. The server also exposes simple function tools for: time / date weather news current facts (Wikidata / Wikipedia) memory lookup (SQLite-backed)

Memory is intentionally tiny. There is a profile table and a facts table. It is not a full cognitive architecture, but it is enough to give TARS continuity: “My name is Phill.” “I live in Austin.” “My timezone is America/Chicago.”

When a prompt contains a memory trigger, the server extracts and stores it, then injects that context back into future requests. It feels like a tiny, fake operating system: a handful of utilities wired together so the LLM always has the right context.

TTS as a First-Class Endpoint

Audio is where embedded systems die. The ESP32 cannot tolerate indefinite streams or chunked responses. It needs a clean end-of-file.

So /tts is designed as a safe, finite stream:

* The server generates the full audio first.

* It sets Content-Length explicitly.

* The ESP32 audio library can stop reading at a precise byte boundary.

I also attach a tts_id header so each spoken reply is traceable. This turns TTS into a debuggable component rather than a black box.

Debugging as a Feature

The server exposes: /debug for device state snapshots /last_text for the last transcript + reply /last for wake scores

This is not just a convenience. It is how I track failures across the pipeline without staring at serial logs.

Timing and Latency

Every /speech call logs timing for STT + LLM. This is the only way to keep the system responsive. If any stage takes too long, I can see it instantly and adjust either model size, tool routing, or text length limits.

The Personality Layer

The LLM persona is defined here, not on the ESP32. This is where TARS becomes a character instead of a voice assistant. The microcontroller only plays what it receives. The server shapes the tone, the cadence, and the attitude.

The joke cue light lives on the ESP32. The sarcasm lives here.

6. The “Infinite Hiss” & The Protocol Pivot

“It's not possible.” “No, it's necessary.”

The “Hiss” turned out to be a mismatch in HTTP standards. The server was sending “Chunked” encoding, but the ESP32's audio library expected a defined file size to know when to stop requesting data.

I modified the server to calculate the exact size of the TTS audio before sending headers. This synchronization, combined with the power filtering on the microphone's line, finally delivered crystal-clear audio with a zero-noise floor.

7. Refinement & Personality

“Humor setting 75%.”

A robot isn't a robot without personality. To move beyond a generic assistant, I utilized the latest Speech Description capabilities in the Google Cloud Text-to-Speech API.

Using the Flash 2.5 Preview model, I passed a custom natural language prompt to the TTS engine to stylize the output. Instead of a standard robotic voice, I directed the model to mimic the specific vocal inflections of TARS from the movie Interstellar: dry, monotone, yet capable of subtle, rhythmic sarcasm. This allows the AI to “act” out the lines with the correct cadence and gravity of the character, all generated on-the-fly. This of course can be disabled within the code with a flag and replaced with a TTS model running locally, I unfortunately am limited by my home servers dated hardware.

To give TARS a physical presence on my desk, I mapped his internal states to an RGB LED: Disconnected: Red Idle: Green Listening: Blue (Brightness mapped to microphone amplitude) Thinking: Pulsing Purple Speaking: Blue (Brightness mapped to audio amplitude)

I also added “earcons”—simple sine-wave tones generated mathematically in real-time by the I2S loop. These play when TARS wakes up or finishes listening, ensuring he feels like a functional piece of hardware rather than just a speaker.

8. Conclusion

“Cooper, this is no time for caution.”

Building TARS was a journey of stripping away the unnecessary. It forced me to appreciate the power of a $3 chip—and the potential sitting in a dumpster.

TARS is now a permanent fixture on my desk. He’s a bit of a Frankenstein’s monster, built from trash and old parts, but he works perfectly. And most importantly, when I'm done talking, I know exactly who is listening: no one.

You can expect all of the project files (C/Python Code, 3D Models, Circuit diagrams) to be uploaded to Github under the creative commons license upon the projects completion.